“There is a way that seems right to a person, but its end is the way to death.” Proverbs 14:12

Death was such an incredible thing to witness, because it was the closest thing I saw to truth.” Ocean Voung

On June 4th, 2022, we celebrated my dad’s life at his memorial. But now, I write about his death. Please know that this blog entry contains difficult details of suffering and death. I encourage you to read it as a means to normalize facing death, and how it is not always good and peaceful. It doesn’t have to be. But I also understand that we are all at different stages in life, and some may need to simply pass on reading this right now. After all, it has taken me months to come back to this blog, and finally choose to write in detail about my dad’s death which occurred 8 months ago. Take care of yourselves. Read on if you like, but it’s okay if you don’t.

I was reminded during the Message of Hope beautifully offered by my pastor during Dad’s memorial, that death does not define a person, and she also reassured me one on one, just after he died when I was so pained by the way he died, that sometimes death is just hard, it doesn’t have to be good. It is indeed, a bit of wisdom: Sometimes, death is just hard. And it has nothing to do with the value of the person’s life who died. Let it be so with grace.

For weeks I was haunted by images of my dad’s suffering, pain, confusion, and difficult death, and even as those memories have softened, I recognize what a privilege it was to tend to and care for Dad in those fragile and tender moments. I witnessed it all, mostly, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I am working through those haunting images, the unfairness, and frustration of it all with the intent to live my life in a way that honors Dad’s legacy. And while his life is indeed what defined him, not his horrible death, it is a topic we need to talk about more. We are mortal beings. Our bodies will acquiesce to an eventual death. All of us will cross the death threshold in one way or another, and we place shame on ways and reasons death occurs, we shy away from its part of our lives, and we embrace fantasies in order to avoid the messy, hard reality of death. Perhaps nothing really, is more truer than death. And as we frequently hear, “The truth will set you free.”

While there are some who bravely talk about this topic, especially when it’s not a “good” death, it’s not talked about enough. We need to normalize it. Humanize it. Dispel fantasies about it, and more. Sacred stories include dying. As Madeline L’Engle said, “We tell stories because we can’t help it. We tell stories because they fill the silence death imposes. We tell stories because they save us.” I love the idea of filling “the silence death imposes.” This blog entry does just that, but I also appreciate the silence death imposes. As you will read later here, that imposed silence was a needed moment and the beginning of my grief-healing. That silence was like an exchange of breath: my dad’s gone, and mine deep, filling my lungs with relief and peace.

My dad died on April 25, 2022. He had spent about 5 weeks in the hospital, then rehab, then back in the hospital. He’d had a stroke from a thrown blood clot, even though he was on a blood thinner to prevent that. He’d developed blood clots in both his leg and lungs, a common occurrence for cancer patients. He had just completed his radiation treatment, which was working, to reduce the metastases- multiple bean sized tumors that had developed in his brain after his lung cancer diagnosis which was detected from regular scans after having beat bladder cancer the year before. The lung cancer was really small, only cellular. There was a 1 in 10 chance it could spread to the brain. “Lucky” Dad got to be that 1 in 10… Still, I was so proud of the way my dad just lived into what he couldn’t control about his new cancer diagnosis and realities. This was very hard for him in life- the lack of control, and yet in these difficult realities, he felt a sense of peace he had struggled a lot of his life to find.

I had to put Dad’s arm around my shoulder and walk him to my car when we went to his scheduled oncologist follow up appointment on March 22. (As I drove to my parents’ house that morning, I shed a few tears over another gut wrenching situation in my life, while worried about what I was to face now. Little did I know that I was now embarking on another grief upon grief in the weeks and months to come.) Dad didn’t think my plan to walk him out to the car would work, even though he said, “You’re going to have to help me” while he leaned against his bathroom counter, skeptical he could make it out. I kept telling him, “Trust me; I’ve got you.” (And I did. Then, and all the way to his death.) As we slowly made our way out of the house, his grip on my shoulder indicated his concern that he (we!) might fall. He kept adjusting his grip, bundling up the material of my sweatshirt in a bunch that got bigger and bigger in his fist as we walked to the car, the side of my torso exposed as my shirt kept gathering in his worried grip. I think it took about 20 minutes to get from the bathroom to the car. I think a lot about that long, but short walk out of his home, knowing now it was his last exit from that loving home I would later spend the months of autumn packing up and reminiscing through, after his death and my mom’s move to assisted living.

I was very worried about Dad the couple of days leading up to that oncologist appointment, having helped sort through his medications the day before, and noticing his inability to balance well, or get around safely. He thought it was just side effects from the brain radiation. (I wonder if his doctors reminded him about stroke symptoms and to not hesitate for one second if he had any inclination of change. He did say during his first hospital stay that he recalled a subtle change in his vision, and only wondered then in hindsight- if that had been the onset of the stroke.) He didn’t take my advice to go to the hospital the day before his appointment, but said he would if his oncologist said he needed to. Sure enough, that was what he recommended. He wanted scans of his brain immediately, and sent him to the ER. Scans revealed several small strokes in Dad’s brain, although it was really just one stroke that had had broken off into different vessels impacting multiple parts of his cerebellum. Dad began treatment, with several ups and downs, mostly feeling discouraged. Physical Therapy took him up and down the hallway with a walker. Speech Therapy worked on his swallowing, a problem that hadn’t surfaced right away. He was weak on his right side, and tended to lean that way while walking. On the second night of his stay, he fell and I got a call at midnight about it. I burst into tears, sitting in my closet so as to not wake anyone, even after the nurse said he was okay. Dad later explained that he thought he was at home, and was calling out to Mom to help him get to the bathroom. I don’t know why he wasn’t on closer monitoring of his fall risk, but he sure was after that…

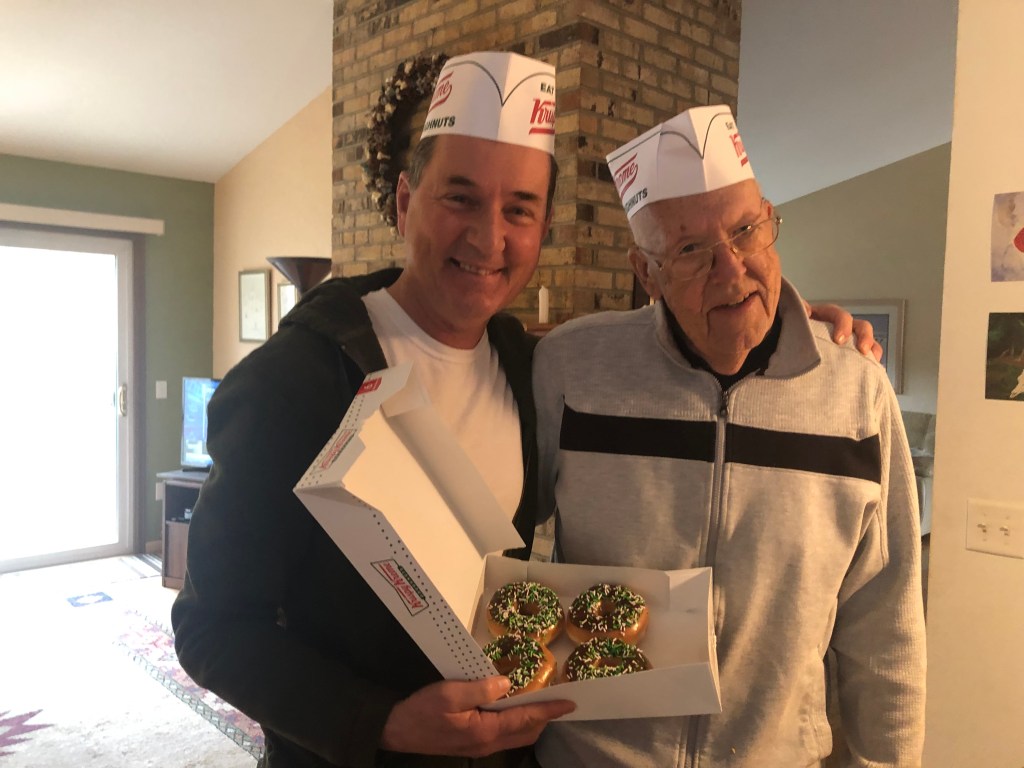

On March 25th, we celebrated Dad’s 80th Birthday in the hospital, and my brother had flown in from out of state to help. Dad was so touched by the cards that were beginning to pile up on his corner counter in the hospital room. (Whoever designed hospital rooms forgot to consider card/flower placement and accumulation…) He loved the digital photo album I put together with photos and birthday messages from each of his immediate family members, and even the family pets. : ) He wore the hand knit beanie with pride his “favorite granddaughter” (his only granddaughter) made for him. He joked with the staff, and immediately became a favorite patient even with his stubborn curmudgeonry. They loved him. He would complain about the care while also being tearfully grateful. He would generalize how “nothing was working” and “everything was terrible” about his hospitalization, while offering gratitude to nurses and therapists. He cried when his loved ones arrived, and cried when we left. About 10 days later he was discharged to rehab, and we held on to hope. Dad would often say, “That’s all I’ve got. Hope and humor.” One of my favorite stories was one afternoon when he had been in the bathroom, and his nurse for the day, Tyler, came in and asked him how it went. He said, “Here I sit broken hearted, tried to shit, but only farted.” Tyler threw his head back in laughter. Dad acted shocked, “You haven’t heard that quote?!” So many times, we were laughing, as much as we were crying and depleted.

But one day when Dad and I were alone, and we had been siting in silence, he broke it with, “I’m scared.”

“I am too, Dad.” I said, not being of any comfort other than being honest. “I promise to face these fears alongside you in the best way I can, and I know our fears differ, but I love you. I will be here with you in all of it.” (Or something like that.) He had mentioned several times, “I am the patriarch. I need to be here.” Instead of patronizing him by saying we had it all taken care of, we recognized his need to be needed. And we did need him. So we told him that. My brother one night said, “Dad, you’re right. We do need you. And, you can trust us to take care of things while you’re getting better.” My brother noticed how Dad relaxed into sleep after he told him that meaningful truth. During a conversation we’d had about steps my brother and I needed to take in case he didn’t survive, I told him, “I can’t imagine life without you, but we will take care of things.” He didn’t need to hear, “Don’t worry. We’ve got it all under control.” He needed to know that it was both. We wanted him here. But we would also take care of the items left undone, the details, and most especially, Mom. His beloved wife, whom he truly adored, admired, respected, and loved. He wanted to care for her until her dying day. (By the way, my parents planned very well for their aging and deaths, with wills, life insurance, long term care insurance, savings, password managers, prepaid burial plans, and more. If you have not done these things, please do. Your loved ones will be grateful!)

One of the things Dad looked forward to most at rehab was being able to see his beloved greyhound, Genny. Dogs were allowed to visit, and we were thrilled. Pictured is Dad seeing Genny for the first time in almost two weeks, worried she’d forgotten about him. She had not. At home, she would smell his boots by his bed and whimper. She looked around for him. She placed her snout on his favorite reclining chair, just waiting for him, and seemed a bit restless if anyone else sat in it. Genny has never been quite the same since he left the home and never came back. She knew. She didn’t engage in her regular zoomies for months after his death, even when we took her to her favorite dog park over the summer. She trotted around, but it almost seemed as though she was thinking, “Maybe he is here. I will look for him.” Dad loved taking her to that park. It felt as if Genny refused to play freely without him there with her. I can report now, however, that she has resumed zoomies, her grief perhaps not quite as heavy as it first was. Dogs are so special…

The first few days of Dad’s intense physical, speech, and occupational therapies in rehab were encouraging, but strenuous. His abilities remained steady, but no significant improvement. Some days were better than others, and his therapists would gleam in his ability to go up and down a step in the gym. “A good sign!” they would celebrate. (Remember the last time one step was a celebration? Toddlerhood.) We began to make plans about walkers at home, and bars to help him in and out of the bathroom, etc. But then he grew weaker. Participating in his therapies was exhausting for him. At one point after he had managed to move from a wheel chair to another chair with such despair and frustration, tears, and depletion, and upon giving him a small shoulder massage afterward, I had to excuse myself discretely to the bathroom and cry. Shedding tears with him wasn’t the issue, and in fact, it was good to do that, too. But this time, I needed to cry a little harder, and do it on my own. To witness my dad in such a struggle was at times too much to bear.

Dad began to eat less, and then not eat all all. If approved by the nurse, I brought in foods I thought might be more appealing to him. I tried to be present at his meals, so I could assist, and then they changed his tray color, indicating he needed someone with him during meals to encourage eating. Many times while there, I would feed him. After three to five bites of applesauce or pudding, with plenty of time between each bite, he would say, “Am I finished yet?” And I always encouraged just one more bite. (Or two, suddenly hyper aware of each of those bites of sustenance. The water, the vitamins, nutrients, going into his body and absorbed in quick desperation. Pause, we should, when we eat, aware of what we are putting in these temporary, invaluable vessels of ours…) Soon he had required oxygen for the first time, and his condition was slowly worsening. Upon ordered scans by a doctor, he was readmitted to the hospital discovering that he had pneumonia, likely caused by silent aspiration due to his difficulty in swallowing. Our hopes that he would move to a sub acute rehab had disappeared, and we were back to square one.

His second stay at the hospital he was much weaker. Instead of physical therapy walking down the hall with a walker, his goal was to simply be able to sit up on the edge of the bed. He did so at one point with PT, and he cried in pain once he had accomplished it. Later his goal was to simply be able to turn his body to the side on his own without assistance. I couldn’t help but remember the goals he’d voiced only days and weeks earlier: “I just want to be able to mow the lawn, or take my dog on a walk again.” Those were now lofty at best. And he couldn’t even talk anymore, but maybe one or two word responses. Mostly, he moaned and groaned. His only hope to have any improvement was to begin a feeding tube, to which he consented. I was reluctant, knowing Dad was the kind of guy more afraid of the conditions he was now facing than death itself. But, he wanted to try it, and it did provide a decent amount of improvement. Doctors were encouraged by his returning strength and diminishing need of oxygen. And so the roller coaster had shifted uphill. With some hope and improvement, Dad agreed to receive the PEG tube, a more permanent feeding tube he could have while going to rehab again soon, and while he worked with speech therapy to be able to swallow properly again. But just before his surgery to place the PEG, a condition called, Hospital Delirium hit hard. He was horribly confused. He pulled out his nasal feeding tube that goes all the way to the stomach, something the staff had feared he might do. After some stabilization, he had the procedure to place the more permanent PEG feeding tube directly into his abdomen. But the procedure itself had worsened the delirium. He was confused, and hallucinating. He had to wear mitts to prevent him from pulling at IV’s and tubes. Hospital Delirium was one of the most awful things I have ever witnessed a loved one go through. Eventually his mitts were removed because he hated them so much, and one of the nurses felt it was actually making things worse for him. (I will never forget that intuitive nurse…) But he pulled at his PEG tube and caused some bleeding. Eventually that improved, and while he wasn’t fully out of the delirium, it had calmed down a bit. And then it was gone.

Then he slept. And he slept, and he slept, and he slept some more. He was awakened for medications, and swallowing therapies. But he could barely talk. I clearly remember one day I was there when his speech therapist came to work with him and his swallowing. She had to wake him up, and sit him up to begin. She explained how the sphincter at the top of his esophagus was not relaxing the way it was supposed to, and so there was too much risk knowing foods and liquids would pile up there and spill over into his lungs. She fed him an ice chip, instructing him to swallow really hard once it melted. She fed him a spoon full of water, having him repeat a hard swallow. Three or four times he did this, and afterward, he was exhausted. Imagine just the simple act of having to swallow, only three or four times, taking every ounce of energy you have. When swallowing equates to running a marathon… I thought back to a few days earlier, when he was readmitted to the hospital, and could still put together a coherent sentence, Dad said to me, “Who really has any kind of significant recovery from the state I am in?” He really wanted to know. He deserved a clear answer. But nobody could say for sure with 100% certainty. So much of our lives is accepting that we just cannot know what the future holds, even with all the information possible. Medicine is a “practice” after all. That day, I could sense the speech therapist’s skepticism that all of this effort was really making a significant difference. Even though I couldn’t really name it at the time, somewhere inside me, I intuited in that moment, that Dad was dying.

Somewhere, deep down inside in a place we couldn’t seem to find, and quite possibly neither could the professionals, we all knew, even Dad, that Dad was dying. But it was subconscious. And truly, nobody really knew he was dying, because there was always a “chance” of improvement. But was there really? And aren’t we all always dying, even if not actively, even as we are living and surviving? Even as both my dad and I told the doctors to be 100% clear, straightforward, and honest about his prognosis, even they were holding onto something while also being transparent. The palliative care coordinator and I had several conversations which were probably the most on par with predictability, even without fully knowing what may or may not happen. But she did know that another catastrophic event would likely be the impetus to transition into hospice care. We just didn’t know what the timeline would be. Days? Weeks? Months? Maybe he’d go to rehab and stay in assisted care/skilled nursing? Maybe he’d be able to go home with in house care? And we did know that the cancer he had, which was not curable, only treatable and manageable, would eventually take his life. But at least with the cancer itself, we knew he could have had at least a couple of years left. Maybe even longer. But with the complications he’d suffered from, nobody knew for sure. Nobody ever knows.

Dad was living his worst fears. He wasn’t afraid to die, but he’d lost his independence, and was living with such indignities he hoped he’d never have to face. The fear of not being able to control things, care for his wife who relied upon him in her state of Dementia, not ready to die, needing more time, needing help with every day basic needs… But Dad had also wanted to at least try the therapies and procedures if there was any hope he could regain some quality of life. Hope is sometimes a dangerous and cruel thing…

“Thank you…” were the last two coherent words my dad said to me before he died. It was the night before he died, to be precise; two simple, ordinary words in a moment of clarity in what seemed like a miraculous break from the confusion, pain, and many setbacks he’d had. I didn’t have to go back and see him again that night before he died far sooner than we, or the medical staff expected, but I couldn’t ignore the strong intuition that told me I just had to. When I think about it now, it must have to do with that mysterious connection people have in close relationships. My mom and I had been with Dad all afternoon that day, but I decided not to ignore this bothersome nudge that I should just go back again and be alone with him that night. When I arrived again, I had only just a little over an hour before visiting hours would end. It was already dark. The hospital was eerily quiet, other than the usual beeps and sounds randomly declaring messages about lives and needs on the floor. Dad appeared to be sleeping- something he had been doing a lot those days, like a newborn baby. (Interesting isn’t it, how the end of life mirrors much of what happens at the beginning: dependency, vulnerability, sleeping many hours of the day and night. New life and end of life are precious, even as they differ.) I reached for his hand, and he turned his head and opened his eyes to see me. He gave a small smile. There was no confusion. I explained why I was back, and that I would just be by his side until I was told to leave for the night. As I was telling him this, I recalled what he had said a few weeks ago, which was, “I feel bad when you’re here because I know it’s a burden, but I’m also so glad you are here, because I feel so alone when you’re not.” His mouth was open and dry from the mouth breathing he’d been doing for weeks now, but he opened it a little more and barely got out the words, “Thank you…” then he turned his head center and closed his eyes again, as I replied to him with something along the lines of, “Of course. I wouldn’t have it any other way; you’re my dad.” I kept holding his hand, saying words of love and affirmation to him here and there, but mostly taking in the dark silence of the room, feeling a weighty, but good presence of my thoughts about his life, our relationship, all wrapped in this one moment, this one, precious hour with him. About a quarter past the hour that visiting hours had ended, the nurse peaked in, and I gave a nod. I unfurled his fingers, the hand I’d held off and on as his child, noticing his bruised and papery skin, and placed it across his chest next to his other hand. “Goodnight, Dad. See you tomorrow.”

The next morning, I called the nurse to check how he was doing. I was worried about him. He’d complained about pain as an 8 on a scale from 1-10 the past few days. He’d been on some pretty strong pain medication. The nurse had a bright and optimistic report, “He’s doing great this morning! He reported his pain as a 4. He followed all of my instructions, and we’re getting everything ready for him to transfer to rehab this afternoon.” I was thrilled. Little did we all know, that instead, hospice would be his destination in only a few hours.

A couple who have been long time friends of my mom and dad were scheduled to take mom to the hospital that day. As hard as it was, I had taken advantage of other’s willingness to help ease the burden of transportation and visitation, and this was supposed to be my “day off”. (Note: Please do this. You must take care of yourself. You don’t have to be there every day. I know you don’t want to “miss” anything. I didn’t either. But there is no shame if you do. It’s not your fault. You know what you can control? Your growth in the acceptance of the Unknown. And, this is what community is all about. My dad had a steady stream of visitors and volunteers. I cannot express enough gratitude for his friends and pastors who regularly visited my dad, checked in with me, and all of our family, and stepped up to help. Accept the help.) Not long after Mom texted me to tell me she was there, I got a call from the doctor. “I’m very sorry to report that your dad has had an unfortunate setback, and I am very concerned about how he will do over the next few hours. He then shifted into medical jargon. Some of it I knew, having worked in a hospital now for over 7 years. But the moment he began explaining, my brain, which loves to hoard information, attempted to process it all, but stopped, while my ears filled with a blockage of what felt like the sound of darkness, like a tunnel of surreality that helps one cope I suppose, in a moment of chaos, or trauma. Once he paused, I noticed this “sound darkness” fade, and his voice clear again, and I asked him to clarify what he meant by “how he will do”. I asked, “Do you mean he might die?” “Yes,” he acquiesced. “I’m not sure he will survive this.” As his nurse had been in the room with him checking his monitors and feeding tube, Dad suddenly vomited, inhaling much of it into his lungs. Massive pulmonary aspiration of gastric content carries a high rate of mortality, and especially in such a fragile state as my dad was in. I get angry about this. Many of us fear drowning, and this was a drowning of sorts. But the staff were expedient upon trying to provide relief, and it wasn’t long, although it seemed forever, until morphine took the suffering and pain away.

I hadn’t showered yet. I put on a couple more garments that would make me more acceptable in public, announced to my firstborn a summary of what I was told, texted my husband, best friends, and pastors, and drove to the hospital. It was a long drive, longer than the 20 minutes it takes to get there, even though I arrived in 20 minutes, and I don’t remember any of it. I quickly paced without running, making my way to the second floor Progressive Care Unit, the hallway seemingly stretching longer than usual (I have had nightmares of this happening before in the hospital I worked in, especially during the COVID pandemic). I noted trays and equipment outside Dad’s room, then coming around the corner to see my parents’ friends standing back while a sea of blue scrubs surrounded my dad, hollering out instructions and demands to each other, mom near him on the other side of the bed. One of my mom and dad’s long time friends, Bill, whom I lovingly call, “Uncle Willie” took me in his arms and offered words of encouragement. I then approached my dad, he reached out his hand, and I took it. He was gasping for air. His body and effort maxed out in a massive attempt to pull in as much oxygen as possible. He had grown so weak over the last several weeks, and yet, it seemed he suddenly had the power of an ox in his body’s instinct to try and survive. Every single muscle working. Head to toe. The doctor reiterated that normally in a situation like this, they would have taken Dad down to ICU and intubated him. But my dad was a DNR. I knew he did not want that, too. So they had the oxygen mask over his nose and mouth, and cranked up as high as it would possibly go. They had suctioned as much vomit as they could out of his mouth and lungs. They could not use the B-pap, as that would have caused more damage to his fragile lungs that were recovering from pneumonia. What a drastic shift from last night, and even from this morning’s cheery nurse report, when he needed very little O2 in his nasal cannula. The crackle of vomit in his lungs increased and decreased in its rhythmic in and out mingling with the air. He looked at me with his longing blue eyes. A couple of times, he tried to reach his oxygen mask with his hand, and I assumed he wanted to say something. But he was so weak, only his finger tips could touch the very bottom of his mask, before his arm would flop back down to his side. (I had nightmares of that moment, wondering what he wanted to say, what was left unsaid.) I also knew how frustrated he had been suddenly not being able to hear very well these past few weeks (a side effect from the brain radiation). He must have felt so alone at times because of that hearing loss, even while being surrounded by people. When his languishing eyes locked with mine, I looked back, a pooling of tears soon to spill, and said, “I’m right here, Dad. I will do right by you.”

After consulting with the palliative care coordinator, and speaking with the doctor, it was time to admit him to hospice care. The PCC assured me that when she asked him to indicate his desire about hospice or more intervention, he had given clear indication that he was done, and wanted hospice. Even as I saw right in front of me, the impossibility for my dad to “clearly” communicate anything, I knew my dad, and I trusted that was indeed what he wanted. The doctor encouraged us to move him to Denver Hospice, which is what he said he would do for his mom (who was in a similar situation), and said we had some time. He could die today, tomorrow, or the next day. The ambience and hospice centered care at DH would be a much more comfortable and peaceful space. But I remember clearly the coordinator telling me that she predicted my dad would die that afternoon. I only wish now that she would have pushed for him to stay put, and I wish I would have done the same. But the lure of a more peaceful setting for him to die, and following the doctor’s recommendation, fueled that dangerous kind of hope.

The nurse began pushing morphine, and over the next hour or so, my dad wasn’t struggling. Finally. Only his body continued to work as hard as it possibly could to breathe. “Air hungry” is what it’s called. The muscles in his neck flared and strained with each and every breath, his neck tendons, and his collar bones more visible with each breath. But Dad’s eyes were closed, and his body still, except for the muscles’ instinctual fight to survive. Yet there was no more moaning, no more longing eyes, no more fear. Mom and I held his hand, and took turns telling him we loved him, and offering other words of comfort. I signed papers with Denver Hospice. We waited for a few hours until DH could come get him. About 30 minutes or so before the ambulance transport had arrived, I noticed Dad’s heart rate fluctuating more. I knew then that his death was imminent. It was something I saw in the the hospital in my work over and over again. Sometimes it would take a while, other times, it was quick. But it was near, no doubt. I don’t know why the staff didn’t recommend we stay put at that point. I don’t know why I didn’t think to insist he stay. It is a regret I hold, and always will. But the staff had made their recommendations over and over again. The doctor had come into the room twice since Dad kept having doses of morphine. They all kept on the same page about moving him. The doctor even expressed that he was encouraged by his lung x-rays, believing he would have more time than initially thought. Sometimes, I wonder if it was a numbers thing- (push him out so we have one less death to report at the hospital). It’s hard to avoid speculating, but I still didn’t doubt the compassion the staff held for us and this situation. I do know it was genuine. And the staff loved my dad. “Carl is our favorite” some would say. They loved his raw honesty, his dry humor, his quick wit. (Also, I think his 80th Birthday photo album I made for him supported a special connection between him and the staff. Even the EVS staff read it and flipped through it along with the nurses and doctors. It just helped bolster my dad’s humanness, his personhood, his life, his past, what made him special, why he was so loved, pictures of him in good health, pictures of his family, all created a bigger reality in their minds than him only as their patient. A quick flip through the album, and suddenly this was less clinical, and more personal. We think bringing photos and personal items into our loved ones’ hospital rooms is for our loved ones themselves, and it is, but guess what? It’s for the staff, too.)

When the hospice ambulance staff finally arrived, Mom and I gave dad kisses and more words of love. Mom was the last one to tell him she loved him as we walked out of the room, and I intended to tell the nurse about his heart fluctuation, even though it had seemed to stabilize at a normal rate again since the half hour ago when I saw the first fluctuation. But she was nowhere to be seen. With another patient, I’m sure, and nobody was at the nurses’s station. If she had been, maybe we would have stayed. We walked down the hall, and headed to the car in silence, leaving my dad to the EMT’s care. I told them to take special care of him. “Oh, we will.” I reiterated, “No, really- please take extra special care, more than you ever have.” They paused as if to break out, just for a moment, from the routine of having done this over and over again, multiple times. We drove to Denver Hospice, crying off and on. When we arrived, we signed in, and as we were directed toward the nurse’s station, a nurse came out of her office and stopped us in the hall. Right then, I knew. The look on her face, I knew before I could form the thought in my head, and then she said tenderly, and along with some caring words, “He died during transport.”

It was just one more thing that had gone wrong, of all the things that could go wrong. (Now, just in case you might be trying to assuage that last sentence with justifications, stop. Let it be. Things went wrong. Lots of things. It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Things went wrong. Many things. Let me have that. Let my dad have that. Yes, let us have the things that went wrong. Thank you. Among the moments of joy we had, we deserve to have what went wrong, too.) I am grateful Dad was on morphine. My hope is that he had no consciousness of the transport that was probably was too rough for him, that may have expedited his death, or perhaps didn’t have any bearing on the timing of his death, but I hope, I trust, because I must, that he did not feel alone, confused, or in any pain when he died. Any other option, that very well could have happened, throws me into despair.

The hospice nurse placed her arms around my mom and me. Mom, looked at me for reassurance, and clarity, “He died?!” Not wanting to have to say it again, but knowing I must, “Yes, Mom. He died.” My mom justifiably balled, and continued to for the next half hour straight. We were escorted to a fire place room. The chaplain came in with us, introducing himself to us. I hadn’t seen my mom cry like this in a very long time. Mom cries a lot, because she’s tender, strong, sensitive, and highly emotionally intelligent. But this was the cry of deep agony over losing the love of her life, and her safety and security. At one point she paused as we sat next to each other on the fancy loveseat, waters being fetched. The chaplain returned, placed water glasses on the table. (The table…I briefly noted in my brain how odd it was to be a chaplain, cared for by another chaplain, the tables having turned.) He sat with us in silence and rolling tears, and intermittent vocal cries of my mom’s deep grief. There was a bit of small talk between the chaplain and myself when Mom’s crying became quiet, but then soon she balled again, and I embraced her from the side, and let her cry and cry on my shoulder. I also thought about what a miraculous gift it was- the clarity my mom had about Dad’s death in this moment, even with her Alzheimer’s. We waited for what seemed like such a long time to go see my dad. Finally the time came, and we were escorted to his room.

“The silence death imposes.” Low light, clean, a cozy room. There he was, nicely tucked into crisp bedsheets that reached to his upper chest, folded over at the top with a nicely made white sheet cuff over the top blanket. His arms placed neatly across, one hand on top of the other. He was wearing a new heather grey t-shirt. “One of my, and his favorite colors in T-shirts,” I thought. A bright white towel was rolled and placed under his chin, his mouth slightly open. His eyes closed, his skin pale. He looked so fresh and clean, even in death. A sign of the tender care and preparation by the hospice staff. I sat down and held onto his cold, still arm. Death is so very still. His body solid, and lifeless. And yet, for me, it was exactly the vision and space I needed of him. Just to see his body at perfect, and total peace. No more struggle to breathe, no more agony. No more indignity, tubes and needles. In this awe, and in this eerie space, I stared at his frozen chest. The images so fresh before of air hunger, juxtaposed with this total relief, I soaked in the stillness, the peace, the lack of suffering, this death-rest, my dad’s body that carried his life and soul for 80 years and 30 days. The vessel that made him the one with skinny ankles, and a strong back. The body that survived Polio, a lightning strike, his hand tremor, his slow, steady gait when he walked down the hall of his home that alerted us to his nearness, his beautiful blue/gray eyes, his full lips that my firstborn inherited, his love of using his hands to tinker with engines and things that my second born inherited, his deep voice, his brilliant mind, his humor… He was gone. Dad was dead. And yet, I was so grateful to be with him right then, in the still, silence of death. It was a gift.

The next few weeks were focused on memorial planning and caring for Mom. I wanted so much for Dad’s memorial to be perfect. I poured my heart out into planning and preparing. I wish my dad could have seen the care, and preparation by so many, and the attendance by those who knew him. How grateful we are to have such a loving faith community. The amount of friends, neighbors, and all who knew him who attended was a testament to the fact that my Dad had lived a life more full than I think he ever realized himself, and more full than many in the world, who might define their lives as full, but only fooled by a kind of false fullness opposite of what it really means. Fullness is authentic by simple, but profound truths in friendship, healthy family, community, love, and connection. And I can promise you there aren’t many churches and pastors who put so much time and personal touches, and tender care into their caring, planning, and eulogies as my faith community. Perhaps I’m biased, yes, but I believe it’s generally true. Many commented that it was the best and most meaningful memorial they had ever attended. It was long, but worth every second.

Dad’s cremains rest in The Foot of the Cross Courtyard at our church home, Calvary Baptist Church of Denver. It is such a lovely space full of reminders of life, as much or more than the reminders of death. A water fountain, flowers, plants, a breeze, the sun or rain, traffic nearby- all reminders of the living, are juxtaposed with that welcomed stillness of death: the columbarium and a common urn, statues, and stones, inscribed names, a bench to sit and be still. Our pastor, Anne, reminded us during the interment that, “So many significant moments in scripture happened outside in gardens!” The courtyard feels like one. One mention in particular touched me in a newly healing way when she said, “It was in the Garden of Gethsemane when Jesus cried out to God – asking God if there was any other way other than to endure this suffering…perhaps a cry Carl himself knew in his days in the hospital and rehab.”

There it is. That is the deepest meaning we can draw from Christ’s suffering. Not atonement, but resonance. That reminder helped ease the haunting memories of my dad’s suffering, something I would grapple with for weeks, and still am. But Spirit fell afresh upon us that sunny morning. And as my brother and I helped my mom pour Dad’s cremains into the common urn at the foot of the cross, Emmy Lou Harris’ (one of my dad’s favorite singers) voice sang out this song, “Someday my Ship Will Sail”. For my boat loving Dad, striving to be satisfied in life, it was the perfect choice. You can listen here:

https://open.spotify.com/track/5jb2TNBSpfn0J5lcT9Nk3b?si=b5480192fb16467e

Psalm 116:15 reads, “Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of his faithful ones.” Have you ever thought of death as precious? Know this: no matter how your loved one dies or died, whether agonizingly, suddenly, tragically, peacefully, unexpectedly, long and drawn out, whether they suffered greatly, or very little, there is no shame, but only preciousness at the final threshold. If your loved one had a difficult death, you are not alone. It’s not fair. Not every death is a “good” one. But death doesn’t need to be good. Sometimes death is just hard. My dad had a hard death, but thankfully, as my brother reminded me, the suffering was mostly all in just that one month of his 80 years. Everything was done to try and prevent a hard death, but it’s just the way it was. There is no reason (read that again- there is no reason), and there is no shame. The truth of death we try to control will always override. As I have tossed and turned at night thinking about this, I have given myself grace in knowing I did everything I possibly could as my dad’s daughter, making decisions, asking questions, honoring my dad as best I could. Sometimes I would still cry out in lament, mostly while driving, apologizing to my dad for they way he suffered and died sooner than he wanted to. It was the most difficult privilege, and the most precious moment, in those 30+ days to care for, and eventually assist in my dad’s death. Even in the exhaustion, time, and witness of such dreadful suffering, I wouldn’t change for one second, the gift of each and every moment I spent with Dad as his life ended.

My beliefs about the afterlife are complex, and not simplistic, easy, or wishful, and certainly not certain. And that’s okay with me, really. That sits better with me than being convinced and question-less about something none of us truly knows. (I could say the same thing about my beliefs in relation to God. I guess that will need to be a different blog.) I also acknowledge the way certainty brings some people a sense of comfort. Even me sometimes, especially as one who longs to “know” stuff. But for things so grand as to be outside our human ability to grasp, for me it feels shallow, and misguided to be certain, for example, that my Dad has a consciousness similar to what he had while living, or that he still has anthropomorphic abilities. Regardless, that is why I feel that memory, is one of the most inestimable of gifts we have as humans- an afterlife in and of itself- perhaps the afterlife- memory-which does carry on, and is indelibly pressed upon my heart. And fading as it may, as it will; impermanent, as all things are, we can still speak to the people we’ve lost in our hearts. It’s not really a matter of whether or not they “hear” us (after all, they don’t have ears anymore), but more about the ethereal relationship we still have with them which latterly exists in our grief and in their death, in our healing, in our humanness, in reminders, in uncanny revelations, encounters in nature, in wonder, in our tears, in the words we still speak to them, in the Essence, in the Soul, in the Mystery of it all, in the legacy and memory of our loved ones.

Dad printed out and framed on his desk a quote I once said: “I would rather embrace the wisdom of mystery than be limited by the vice of certainty.” I love that we shared conversations, pondering, reverence, and wonder about Mystery…

Dad’s death was hard, but his life…was extraordinary. Peace to you, if you, too, struggle with the suffering and/or difficult death of a loved one. Circumstances such as disease, aging, choice, accidents, etc., can vary of course, leading to death. But may you know deeply, that there is no shame, and no judgment. Lament, cry, raise your fist with the “whys” as you need. But the threshold of death itself is just truth. Sacred, but nothing more than truth.

Carl Anthony Ramay 3/25/1942 ~ 4/25/2022

Dad’s Memorial Service: https://youtu.be/wWSInIUpL0M

Discover more from Regardful Reverend

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

What an eloquent, honest, anguished, beautifully detailed description of your dad’s death, Brenda. Thank you. I hope many people read this…this is wisdom and truth we all need to hear.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Anne. And Thank YOU! ; ) For your role in all of this…

LikeLiked by 1 person

So well written and heartfelt. You truly are a compassionate mystic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Compassionate Mystic” is quite a compliment. Thank you, Barbara.

LikeLiked by 1 person